“We were told we had to make ourselves as comfortable as possible and there would be transport to take us home. We were wading out to this boat and some German planes came over and they bombed the boat. They bombed everything that was around. One of these bombs went down the funnel of this boat – we at least thought it looked very much like that. It just went bang. And that was it. Our transport home had gone.”

Tommy Brabban’s account of what happened on the beaches of Dunkirk was just one of the stories we received about the events surrounding the evacuation of allied forces in 1940.

Facing potential defeat by Hitler’s army in May that year, thousands of men retreated and found themselves stranded on the beaches of Dunkirk, northern France. Between 26 May and 4 June, 300,000 British and French soldiers were rescued when destroyers and small civilian vessels, such as fishing boats and car ferries, came to their aid. Winston Churchill hailed it as a miracle.

To mark the release of Christopher Nolan’s film, we realised that many Guardian readers have their own wartime stories to tell so we asked you to share your letters, diaries and photographs from any relatives or friends who were involved. Among those we received were stories about the bravery of those at the rearguard, on the beaches or on one of the many civilian rescue boats in the Channel.

Before the evacuation

Eva McIntosh: ‘Dunkirk had just been bombed’

British Expeditionary Force (BEF) nurse

Submitted by great-great niece Diane Watt

Born in 1888 in Glasgow, Eva McIntosh trained as a nurse in her 20s and joined the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service. She went on to serve in both world wars and retired after more than 30 years of service. She died in 1977 aged 89.

On 19 May, acting matron McIntosh and the sisters of the 2nd casualty clearing station left the village of Beaucourt-sur-l’Ancre as part of the withdrawal of allies from France. Writing retrospectively about what happened, she detailed passing through Dunkirk and witnessing the events prior to the siege of Calais.

22.5.40

By 8am an ambulance was ready to take the nine sisters with Padre Hobson Matthews in charge. We were to proceed to Dunkirk. At this point we had to abandon our heavy baggage. We travelled rapidly and at Bergues, where headquarters were stationed, our orders were changed. We were told to proceed to Calais. We passed through Dunkirk about noon, it had just been bombed and at one part a huge fire was blazing. Between Dunkirk and Calais we were delayed three hours, as we were refused permission to cross a fortified bridge.

23.5.40

At 10am we left for the dock, on arrival there had to immediately go to the air raid shelter as the alarm had sounded. About 11.30am we went on board the City of Christchurch, a cargo ship carrying 2,000 troops and officers, 120 evacuees and the nine sisters. Just before sailing we witnessed an air battle and saw two enemy aeroplanes brought down. We were bound for Southampton via Dover, convoyed by a destroyer with Hurricanes flying overhead. There was no accommodation on board, but Captain very kindly gave us his cabin. One of the officers also allowed us to use his that night.

On the beaches

Tommy Brabban: ‘I managed to find a tin of asparagus’

Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) private, working as a driver

Submitted by son Peter

Tommy Brabban was 35 when he was called up in the summer of 1939. He left the family home in Tantobie, country Durham, leaving behind his wife and three children.

As part of the BEF he was sent to Belgium and after the German offensive he joined the retreat to Dunkirk. Because of bad luck, the ship he was supposed to get on was bombed and sank, and his unit became stranded on the beach for nine days.

While hiding under an ambulance van for cover, Brabban discovered a tin of asparagus. He brought it back to his unit and shared it among 12 men – each getting one piece. He said: “We never thought anything tasted so lovely in all our lives. And it was stuff I hated! But never mind, it was something.”

When the men were rescued and the ship pulled in to Dover, Brabban recalled how people on the quayside threw loaves of bread to them and that they fought for it, they were so hungry. Despite being showered with gifts by the public most of the men were ashamed at how they were beaten.

Richard ‘Dick’ Hughes: ‘The hospital ship we left was blown up’

BEF sergeant

Submitted by son Matthew

Richard Hughes was 24 when he and his men stood in line to wait for their turn to be evacuated. Born in Middlesbrough in 1915, he left school to work at 13 when his father died. After the war he became head salesman in the furniture department of a large store in Liverpool. His family emigrated to Canada in 1954, where he died at the age of 58.

On the beaches of Dunkirk, Hughes was told by an officer they would have to wait. Under fire from German fighters and Stuka dive bombers, Hughes could wait no longer and organised his men to build a raft. They paddled out to the vessels they could see offshore and made it to a hospital ship. But the officer on deck said the ship was leaving and they should make their way to another. While making their way to another ship, the hospital ship they had just left was blown up and the survivors killed in the water by machine gun fire. Finally, Hughes and his men made it to a passenger ship, which brought them home.

In the Channel

Thomas Causer: The sea was a ‘burning hell’

Royal Navy officer on the HMS Grenade

Submitted by son Charles

Born in Glasgow in 1919, Thomas Causer joined the Royal Navy in 1938. After the war he married, had six children and worked as a supervisor for an insulation company. He died in 1969 from an asbestos-related disease.

During the evacuation at Dunkirk, Causer was on the destroyer HMS Grenade when it was struck by a bomb that had gone down a funnel into the boiler room. He managed to escape into the sea, but was badly burnt from an oil spill that had been set alight by the explosion. He described it as a “burning hell”.

Causer was picked up and taken to a military hospital in Kent. His parents, who could not afford much, were sent rail tickets to visit him; the journey took 36 hours from Glasgow to Kent. During his time in hospital, he spent three months bathing in oil to stabilise his injuries. During an operation, Causer was blown off the operating table when the hospital was hit by a German bomb. The piece of shrapnel that damaged his right arm was given to him by the medical team as a souvenir and is still in the possession of his family today.

Support at home

John ‘Jack’ Avery: ‘We thought the war was lost’

Born at Fenham barracks, Newcastle upon Tyne

Submitted by son Trevor

John Avery, known to most as Jack, was born at Fenham barracks in 1926; his father was a soldier who had fought in the first world war and was groundsman for the barracks sports fields and parade ground. Avery turns 91 this year.

At 13, he was still living at the barracks when survivors from Dunkirk arrived by train. He said: “They looked terrible. Many didn’t even have boots on. It was frightening to see. We thought the war was lost.” Avery was called upon to run errands for the soldiers, such as buying them fish and chips. In return they gave him French coins they had brought back with them.

Speaking of his experiences, he said: “Even now, war should always be a very last resort. Very, very last resort.”

Those left behind

Stefan Moszynski: Fought in the rearguard defence

Polish army reservist

Submitted by sons Peter and Michael

Stefan Moszynski was born in 1908 in Lemberg, now the Ukrainian town of Lviv, and saw the start of the first world war on his sixth birthday. He was working at the Polish National Bank in Paris in 1939 when he was mobilised in France as a Polish cavalry officer reservist. He joined the 10th Polish Mechanised Cavalry Brigade in France and was ordered to protect the French Sixth Army near Dijon in 1940 as part of the rearguard defence of the evacuation.

Out of fuel and ammunition, and surrounded on all sides, they were ordered to escape to Britain in any way they could. While deciding what to do, a Rolls-Royce appeared with Moszynski’s old friend in it – the son of the Polish ambassador to Argentina. Asked what he was doing, Moszynski explained his desire to go to Britain to continue the fight. His friend asked him to go to Buenos Aires so they could see out the war together, but Moszynski politely declined, so his friend arranged for his chauffeur to syphon petrol into his motorbike.

Later on his journey to get a boat, Moszynski and his unit went to a French army depot and asked if they had any equipment. As seen from an order of requisition dated 20 June, he was given a motorbike to get him to Bordeaux and eventually on one of the last boats out of France.

Moszynski became a tank commander in the Polish 1st Armoured Division, attached to the Canadian Army Corps. In 1945 he was stranded on the western side of the iron curtain and settled in Britain. He is survived by his two sons and daughter.

William Savage: ‘I thought we were going to be shot’

Gunner in the Royal Artillery who became a PoW

Submitted by son Brian

William Savage was born in Woolwich in 1922 and was an apprentice carpenter. He was a gunner in the Royal Artillery and his unit was told to retreat as they became surrounded by the German army. Ordered to destroy their guns and fall back, Savage and his men hid in a ditch by the road to avoid detection by an approaching German column.

Unfortunately, the German convoy stopped and they were captured. Savage said: “I thought we were going to be shot.” He spent five years as a PoW in Stalag VIII-B and was made to work in coalmines in Poland. Towards the end of the war, he and the other prisoners were made to march through snow ahead of the approaching Russians, his carpenter training enabled him to build a sled to pull their gear on.

John Edwards and his cousin Llewellyn Lewis: Fought in the rearguard defence

Privates in the Royal Welch Fusiliers who became PoWs

Submitted by John’s daughter Lynne

Both John Edwards and his cousin Llewellyn Lewis fought in the rearguard defence with the 1st Royal Welch Fusiliers (RWF). Edwards was born in Ruthin, north Wales, in 1911 and was an officer’s groom. Lewis was born near Dolgellau, north-west Wales, in 1919 and was called up at the start of the war. He was 20 when he was captured; Edwards was 28.

On 26 May Edwards and Lewis were far from the beaches of Dunkirk. They had been ordered to stand and fight “to the last round and the last man” in an effort to slow the German advance while others were evacuated. The 1st RWF fought at the small town of Saint-Venant and nearby villages, retaking bridges over important waterways. However, with the Germans still holding other bridges, the company was surrounded, suffered heavy casualties, and the final men were captured in an attempted breakout that night.

Edwards, Lewis and the other captured soldiers were marched towards Germany with little food and water and were eventually taken to Toruń in Poland. Edwards spent the rest of the war in captivity working as a PoW farmer. He returned to Britain in 1945 skeletal and was unrecognisable to those who knew him. Lewis died in Stalag XX-A in 1941, aged 21.

Bernard Pheasant: Fought in the rearguard defence

Corporal in the Phantom unit of the BEF

Submitted by son Peter

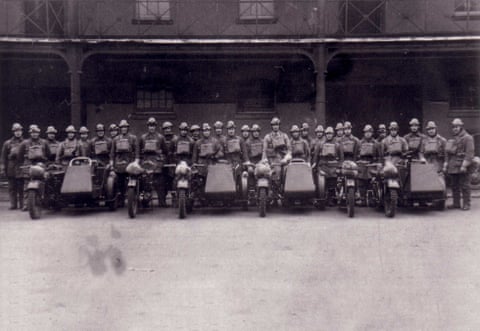

In 1938 Bernard Pheasant joined the Queen Victoria’s Rifles unit of the Territorial Army and was seconded to the Phantom unit to undergo advanced reconnaissance in France in 1940. He was part of a team of motorcyclists who fought the rearguard in defence of Dunkirk and De Panne and were in charge of keeping order on the beaches.

On 31 May, when the evacuation was coming to an end, Pheasant and his section were told to get away if they could. They found a small rowing boat drifting on the shore and after finding that none of them knew how to row, managed somehow to get out to the destroyer, HMS Express. They climbed up the scramble nets hanging over the side, were given cheese sandwiches and cocoa by the sailors and were sent below to sleep.

Next morning, they hurried up on deck hoping to see England at last, and found they were still off Dunkirk as the ship’s crew were hoping to pick up a few more people. On 4 June the ship left for Dover and Pheasant returned home in time for Christmas. In 1943 he relinquished his commission owing to ill health and was given the honorary rank of captain. He went on to a successful career in engineering, married and had three children. He died in 2009 in Somerset at the age of 92.